This article was originally published in Italian on Gamesource.it in 2009.

It was 1999 when the elegant and mysterious Koudelka Lasant made her debut on the grayish console of the time. For those unfamiliar, Koudelka, a historic flop from SNK and the development team Sacnoth, was only the beginning of a series destined to rise to prominence five years later under the Aruze banner and the development of the newly formed Nautilus (now known as feelplus, the creators of Lost Odyssey). The story of “Uru,” however, deserved to be told.

Manchuria, 1913. The daughter of a prominent clergyman is under escort, entrusted to Japanese authorities. Her name is Alice Elliot, a renowned prodigy and daughter of the equally famous and devout Morris Elliot, an internationally acclaimed English exorcist. A few months prior, the two had traveled to Rouen to meet with Father James O’Flaherty to discuss the mysterious disappearance of some arcane texts from the Vatican archives. Unfortunately, they were attacked by a peculiar individual: a gentleman in a top hat and tailcoat who, with just a wave of his hand, tore Father Morris to pieces, sparing only his daughter. Despite her young age, Alice had developed unparalleled exorcising powers in early 20th-century Europe and, with the Vatican’s blessing, served as an intercessor in the name of God.

Manchuria, 1913. Yuri Volte Hyuga, a young man of mixed Russian and Japanese heritage, boards a train driven by a mysterious voice that has been insistently guiding him, leading him into trouble. Yuri, however, is no ordinary boy: he is a Harmonixer, a human capable of fusing his earthly essence with that of elemental demons. Orphaned at just 10 years old, Yuri has been wandering the East, following the territories once visited by his father, a soldier in the Japanese army, seeking revenge. Yuri believes his father is responsible for his mother’s untimely death.

What could possibly connect a priestess devoted to God’s cause and a demon-afflicted boy cursed by his own bloodline?

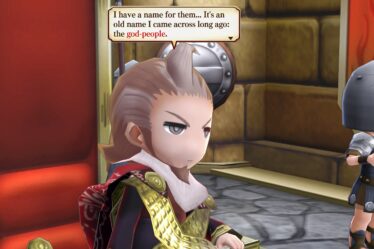

This is the premise of Shadow Hearts, the spiritual successor to the ill-fated Koudelka, set 15 years after the events of its predecessor. The game offers a functional and well-characterized roster of characters. Like Koudelka, the Sacnoth title makes gloomy atmospheres and dark humor its hallmark, with a narrative undertone reminiscent of Lovecraft, all while maintaining the historical mystique typical of the series. Set just before World War I, between the East and the West, the game leverages historical events, locations, and figures to introduce the protagonists’ stories and develop the narrative within a credible and coherent historical and geographical context.

The events experienced alongside the ragtag group of Harmonixers are always tinged with a grotesque and somber tone, far removed from the more common Japanese productions focused on fantasy and “kawaii” elements (anyone say Tales of?).

Fortunately, the game never feels dull or exhausting despite its heavy themes, thanks to a script—particularly its dialogue—characterized by dark humor and hilarious irony. It’s these sketches, the banter between protagonists, that often define their personalities and unique traits, making you feel part of a close-knit and well-matched group. Excluding two of the six protagonists, the characters are all highly believable in their uncertainties, limitations, and dreams, enough to endear even the most jaded player, especially in the final moments.

Of course, in the world of Shadow Hearts, monsters and demons are the order of the day, and folklore and superstition have overtaken logic—a time shaped by the dulling of reason by popular tradition and the Church itself. Yuri and his companions’ adventure spans a mere 20-30 hours, a surprisingly short duration for a Japanese-style RPG, and suffers from some issues related to accessing the few side quests. The game is divided into two historical and geographical periods: initially, we travel through Asia before moving to Europe. This division, if certain unstated conditions aren’t met, prevents players from achieving 100% completion.

While Koudelka adopted a battle system reminiscent of tactical games of the era (or its cousin, Parasite Eve), for Shadow Hearts, the developers introduced a series of twists on classic JRPG gameplay that are decidedly flavorful, setting the title apart from the many mass-produced RPGs. The battle system, for example, while turn-based, features a unique element: the Judgment Ring.

Dubbed “Sacnoth’s stroke of genius,” the Judgment Ring is a disc that appears in the upper right portion of the screen once an action is assigned to a character, such as a physical attack, offensive magic, or the use of a healing item. Inside this disc are various colored cones, the number of which depends on how much the game wants to challenge the player’s success. Depending on the player’s timing—stopping a clockwise-spinning needle within these cones—the command will execute (with bonuses if the needle lands in “hot” zones, marked in red and naturally harder to hit). Thanks to this small addition, the outcome of battles isn’t solely based on the party’s stats but also on the player’s actual skill, requiring Swiss precision and quick reflexes to face the many Lovecraftian creatures that stand in their way.

Another interesting feature of the gameplay system is the introduction of a new numerical energy bar alongside the traditional HP and MP: SP, or Sanity Points. Every action taken in the presence of demonic creatures costs the characters some mental sanity, strained by the psychological stress of facing supernatural beings and surreal situations. Naturally, the amount of psychological resilience varies from character to character: Yuri, accustomed to dealing with demons of all kinds, is practically immune to sanity depletion, while the gentle Alice is one of the least accustomed to such horrors. When the sanity bar depletes, the player loses control of the affected character, who goes berserk, executing random commands on any on-screen target, friend or foe. This situation can be remedied with calming items.

Another entirely original feature lies in the method of recruiting Yuri’s various elemental demon forms. To level up the protagonist’s demonic states, players must collect “Malice,” a malevolent energy released from the corpses of defeated enemies. Once enough Malice is gathered, Yuri can enter the “Graveyard,” a physical cemetery within his soul, via the menu. Here, the Harmonixer comes to terms with his reality, confronting his nature and growing familiar with his demonic abilities as the story progresses. However, Malice doesn’t only affect Yuri positively: for the first part of the game, the accumulated Malice must be “discharged” by facing a foe in the Graveyard, or else Yuri will encounter an unbeatable enemy in random map encounters. All of this is seamlessly integrated into the narrative, and it’s refreshing to see the game bend to the script’s demands rather than the other way around—a practice that seems rare in modern JRPGs.

The difficulty and learning curve of the title are well-balanced, with no unjustified spikes in challenge—already relatively low—to report.

Technically, Shadow Hearts doesn’t seem to aspire to compete on powerful hardware like Sony’s black monolith. The reasons lie in the project’s history, initially destined for the PS1 and hastily moved to the PS2 when development was nearly complete. The game exhibits all the characteristics of 32-bit JRPGs: fixed camera angles, pre-rendered backgrounds, decently characterized polygonal models, and a barely sufficient number of special effects in battle scenes, which, while not drastically improving the game’s technical appeal, allow for a good number of character-specific animations. Paradoxically, this polygonal simplicity works in favor of the game’s resolution and visual clarity.

The polygonal models of the protagonists are rudimentary, but fortunately, cutscenes rarely zoom in on them, as most of the narrative is conveyed through dialogue boxes accompanied by character artwork. Thumbs up, however, for the brief and sporadic FMVs that highlight key story moments, though the English dubbing leaves much to be desired.

One of Shadow Hearts’ strongest aspects is undoubtedly its soundtrack—beautiful, atmospheric, and dark, a unique asset for the series. Yasunori Mitsuda (Chrono Cross, Xenogears, Soma Bringer, World Destruction) and Yoshitaka Hirota have managed to recreate the world of Shadow Hearts in their compositions, pulsating and bloody in its somber and chilling nature, ranging from industrial to techno/electronic rhythms. Of course, there are also touching and melodic pieces, such as the game’s ending theme, “Shadow Hearts,” or the track that would become the series’ theme starting with this installment: “Icaro.”

Shadow Hearts is not a must-play, nor a classic of the genre, nor a title we’d recommend to a newcomer to Japanese RPGs. It’s also not a game we’d suggest to someone looking to explore the PS2’s capabilities. However, it is a small, rough diamond, undervalued and forgotten by many. Yet, from the simple foundations of this title, a few years later, we would return to Yuri and his story in Shadow Hearts 2: Covenant, where the series would reach its qualitative peak.